In the modern scene of Java, applications can be written quickly thanks to many third-party frameworks that allow developers to componentize, isolate, and layer pieces of code by doing all the boilerplate for them.

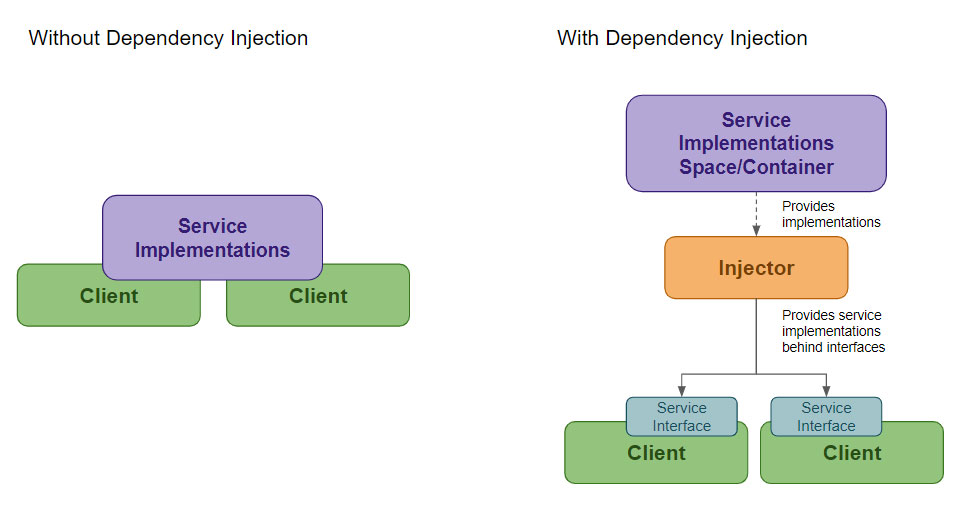

One of the popular terms in this regard is Dependency Injection. In summary, the goal of this concept is to decrease coupling between layers by making service clients less aware of service implementations by having an injector/indirection layer provide the service for them – instead of having clients instantiate the services themselves. This also has the added benefit of nudging developers to minimize and contextualize interactions between services and clients. The following image describes the concept and its difference from the practice it departs from:

Frameworks such as Spring or extensions such as Java EE provide this indirection in the form of containers that provide clients with implementations, while only keeping the clients aware of the corresponding interfaces.

Since Java 6, Java SE actually has had a somewhat bare-bones implementation of this concept. This feature is called Java SPI (Service Provider Interface). Although its name suggests that it might satisfy the requirements of dependency injection, it actually covers far less boilerplate and functionality that third party frameworks have to offer – hence, “bare-bones”.

However, it still has its uses.

Starting Using Java SPI

Java Service Provider Interface, or Java SPI, provides Java SE programming with a way to register implementations to interfaces through metadata. This is actually one of the ways with which Java libraries and utilities communicate with one other.

Aside from the actual service interfaces and implementations, there are only two components to be aware of when starting using Java SPI:

| Component | Description | Dependency Injection Parallel |

|---|---|---|

| Metadata Registries | The registries in which implementations of interfaces are declared | Service Implementations Space/Container |

| ServiceLoader | The class that serves the implementations of the specified interface | Injector |

1. Creating the Service Interfaces and Implementations

Before the registries can be created, there have to be service interfaces (which can also be abstract classes) and implementations.

To better ease into SPI, the pieces of code shown appear in a single Maven project, as the predefined directory structure helps.

The following code shows a simple service interface to be used as our example:

package com.pizza

public interface PizzaService {

String orderPizza();

}

Then, the following pieces of code show two implementations of the above interface:

package com.pizza.impl

public class ItalianPizzaService implements PizzaService {

@Override

public String orderPizza(){

return "Received [pepperoni pizza] from [Italian restaurant]!";

}

}

package com.pizza.impl

public class AmericanPizzaService implements PizzaService {

@Override

public String orderPizza(){

return "Received [burger pizza] from [American restaurant]!";

}

}

2. Filling in the Metadata Registries

The contract for registering service implementations are as such:

- Create a file For each service interface to which implementations are to be registered; these files will be named and located as META-INF/services/<fully qualified class name of interface>

- Inside of each service interface file, each line would list the fully qualified class names of the implementations

Following the above requirements, the following file is made in the resources directory of the project:

META-INF/services/com.pizza.PizzaService

To describe the behavior of multiple implementations in the proceeding steps, both implementations are registered into the file – the above file then contains the following:

com.pizza.impl.ItalianPizzaService

com.pizza.impl.AmericanPizzaService

3. Getting the Registered Services via ServiceLoader

Finally, services can be retrieved via the ServiceLoader provision class, which returns instances of implementations based on the services registered via the metadata.

Though usage of the ServiceLoader class is usually abstracted by a manually written provider class (usually to introduce logic for purposes such as selecting/qualifying the right service), this example mocks client code via the following main method:

package client;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.ServiceLoader;

import com.pizza.PizzaService;

public class Client{

public static void main(String[] args){

// initialize a loader

ServiceLoader<PizzaService> pizzaServiceLoader = ServiceLoader.load(PizzaService.class);

// a loader is iterable!

for(PizzaService oneImpl : pizzaServiceLoader){

System.out.println(oneImpl.orderPizza());

}

}

}

The output of the above code would then be the following:

Received [pepperoni pizza] from [Italian restaurant]!

Received [burger pizza] from [American restaurant]!

The Power of SPI

The previous section shows how SPI provides services through metadata registries, and though it somewhat satisfies the concept of Dependency Injection, one of its best features is that allows distributed development as registries can be located even in java libraries in the classpath i.e.:

- registries in META-INF/services folders in JAR dependencies are also picked up by ServiceLoader

- interfaces and services declared in a metadata registry can involve interfaces and classes from other JAR dependencies

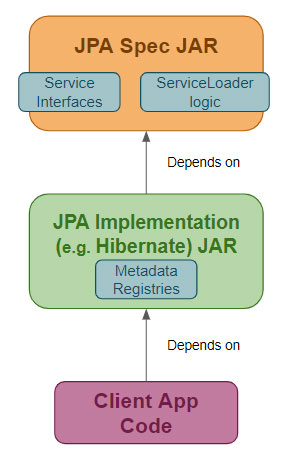

This is usually leveraged by Java Extension specifications and implementations such as JPA (Java Persistence Annotation) – as the specification -, and Hibernate – as the implementation in the following style:

Other examples of usages of SPI usually have “Provider” in their name, such the following Java utilities:

- LocaleNameProvider

- TimeZoneNameProvider

- DateFormatProvider

SPI can also be a helpful temporary, last-resort tool when breaking monoliths into smaller pieces in preparation for turning them into microservices, as it’s a very lightweight and malleable solution.

Get creative!